Conspicuous in the chert - synangia of

Scolecopteris

Parts of the large fronds of the Psaronius

* tree ferns

are well-known fossils

from several locations worldwide, and they are abundant in some of the

chert variants from the Lower Permian Döhlen basin. When preserved

3-dimensionally,

as in chert, they are called Scolecopteris,

else Pecopteris.

As a

characteristic feature they bear groups of sporangia fused at their

base, called synangia, on the lower side of the pinnules. The build of

the synangia is not uniform among the species of Scolecopteris:

They may be thin-walled and largely

enveloped by the recurved margin of the pinnule and thus protected

(Fig.1), or

free-standing and thick-walled (Fig.2), thus protecting themselves, or

something

in between. The more

thick-walled forms were probably hard and dry like the seed capsules of

many extant flowering plants and therefore decaying more slowly than

the pinnules bearing them. Therefore the synangia

are often the most distinctly

seen parts of the whole plant. This should make them suitable for

the identification of species.

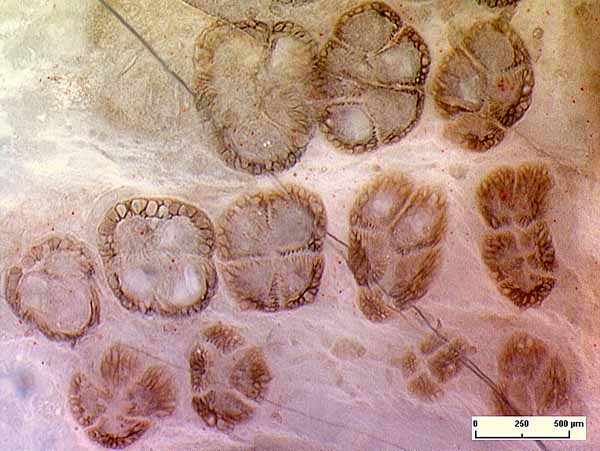

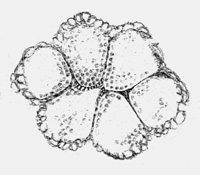

Fig.1: Scolecopteris

pinnule cross-section with synangia protected by fringes extending from

the pinnule margins, seen on the natural surface of a chert

layer fragment found near

Perdasdefogu, Sardinia, and resembling Sc. elegans, a

common species from Döhlen basin. Pinnule width

1.7mm.

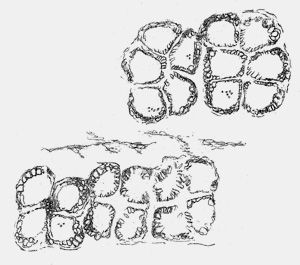

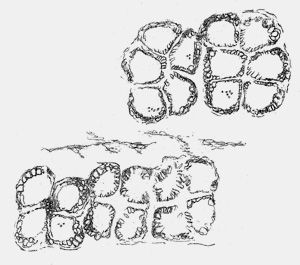

Fig.2: Scolecopteris

pinnule cross-section with exposed synangia composed of

thick-walled sporangia, less-common variety from

Döhlen basin, drawing after polished chert face. Width of the pinnule

1.6mm.

The identification of species by their

synangia turns out less practicable than

expected, with the

problems being partly genuine and partly generated by palaeobotany

itself. The scarce fossil material available to some researchers in

this

field led to the statement that the synangia of the "maggot fern"

Scolecopteris elegans

were composed of 4 to 5 sporangia and had "radial" or "bilateral"

symmetry. Such

statements, by repeated quotation, have found their way into the latest

publications

on the subject [1,2,3] despite of glaring evidence for the contrary:

Symmetry is no useful

concept here since synangia of various symmetry types, including no

symmetry at all, are usually found together on one pinnule (Figs.3,4 ),

and the

number of sporangia varies between 3 and 6 (Figs.3-8), with rare cases

of 2 and 7.

This should have been a well-known fact since the early work by Zenker

[4], who found the absence of a common symmetry so remarkable that he

drew a variety of synangium cross-sections, including non-symmetrical

ones.

Zenker

was readily referred to for the introduction of the name Scolecopteris

but apparently his paper [4] was not thoroughly inspected.

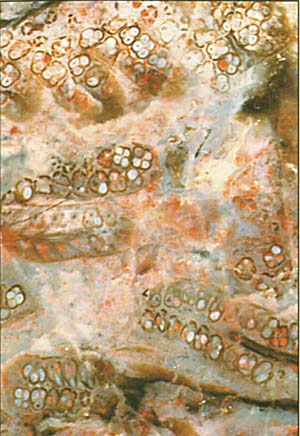

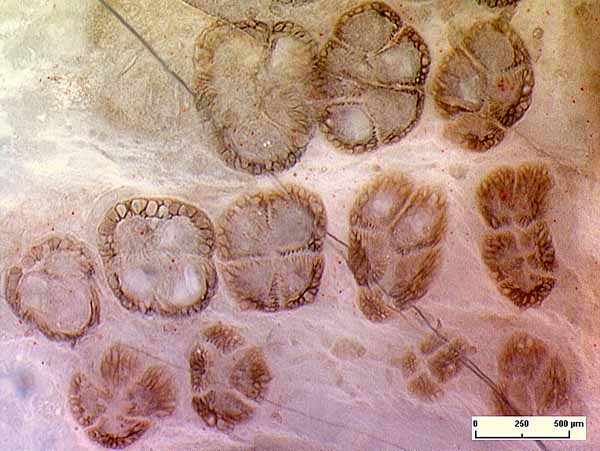

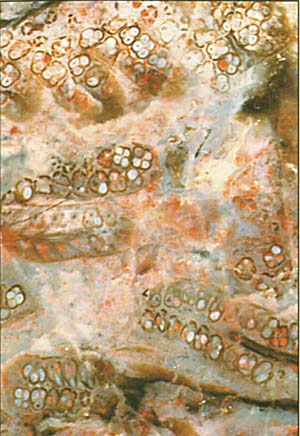

Fig.3,4: Usual aspect of Scolecopteris

synangia in cross-section: symmetry of various

type or absent. Photographs: H. Sahm.

Fig.3 (left): The two rows of synangia below are on one

pinnule. They

have been cut more or less near their tips.

Fig.4: With of the picture 1.23mm.

Another inappropriate notion surviving in the literature on Scolecopteris is

that of "spindle-shaped" or fusiform sporangia [3] although the

cross-sections of

the sporangia are not even approximately circular, as seen here.

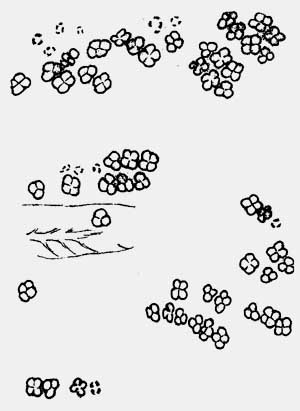

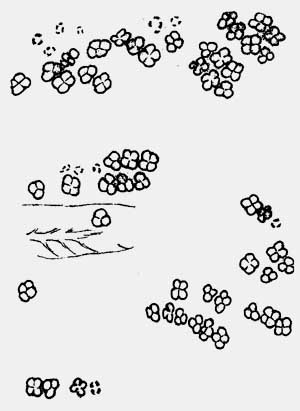

Figs.5,6: Chert face with

conspicuous array of Scolecopteris

synangia cross-sections on pinnules hardly visible

owing to decay [5]. Only the well seen cross-sections in Fig.5 have

been included into the drawing. Width of the picture 9mm. Photograph:

W. Schwarz.

Figs.5,6: Chert face with

conspicuous array of Scolecopteris

synangia cross-sections on pinnules hardly visible

owing to decay [5]. Only the well seen cross-sections in Fig.5 have

been included into the drawing. Width of the picture 9mm. Photograph:

W. Schwarz.

The good visibility of the synangia in Fig.5 may be due to

the higher decay resistence of the possibly dry and hard sporangium

walls compared to the soft pinnule tissue. There is something else

which is remarkable about Fig.5: Among the 65 synangia

seen here in cross-section, 25 are less-common ones with only 3

sporangia,

and none is seen with 5.

The large number of synangia can easily mislead to the guess that Fig.5

is possibly a

representative part of the sample with a particular

species

whose synangia are composed of 3 and 4 sporangia only. However, there

are

synangia with 5 sporangia outside the frame of the picture, which may

serve as a warning not to draw conclusions hastily. This applies also

to the preliminary statistics in the table below, based on 69 chert

samples with synangia seen in cross-section.

The

numbers n of the n-fold synangia seen in one chert sample are listed in

the first line of the table. The second line is the number of related

samples.

3 4 3 4

5 3 4 5 6

4 4

5 4 5

6 4 5 6 7 5

6 5 6

7

14

10 3

15

19 5

1

1

1

Note that this does not mean that a type characterized by 4-fold

synangia only has been

found in 15 samples. Additional cut faces would

probably provide synangia

with n = 3 or 5 .

As

a general observation from the Döhlen basin, synangia with 4, 5, and 6

sporangia are often seen in close vicinity, on the same or neighbouring

pinnule (Fig.7).

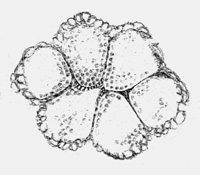

Most

sporangia were empty when the fronds or pinnae fell into the water and

became silicified but some were still filled with spores (Fig.8). Here,

the spores are not lying in the sporangia loosely but are seen to be

still arranged in some original order. As another remarkable feature of

the sporangia in Fig.8, the walls have

completely collapsed where they mutually touch so

that they are seen in cross-section as a mere thin line. (Compare

Figs.4,7 where the individual walls are still seen.)

Fig.7 (far left): Scolecopteris

synangia of different type on neighbouring pinnules, as seen on the raw

surface of a chert sample. Width of the picture

2.2mm.

Fig.8: Synangium with sporangia completely filled with immature spores

and with walls partially collapsed into thin foils. Width

of the synangium 0.9mm.

The

observations lead to the conclusion that notions like symmetry of the

synangia and spindle shape of the sporangia are not helpful for the

identification of Scolecopteris

elegans

and for differentiation between similar strains closely related to it.

"Rotational symmetry", which means an n-fold rotational axis in the

synangium, is a characteristic feature of a group of Scolecopteris species

including Sc. globiforma

and Sc. unita

[6] but not of Sc.

elegans.

Other features of

the synangia are more suitable for differentiation between maggot fern

variants or species:

The pedicel

is usually much shorter than wide and thus hardly visible, or

it can be

rather conspicuous. The sporangia can be thick and short or narrow and

tapering. Hairs on the

sporangia are well known from Scolecopteris

species found in "coal

balls" in North America [7] but have been found in the Döhlen basin in

only two samples hitherto. An evaluation of

the more useful but rare or elusive features of the synangia in the

cherts of the Döhlen basin has not yet been done. Considering that lots

of chert samples with Scolecopteris recovered

in the 1990s have been stored away and not even looked at, it is well

possible that some correlation between synangia features and fern

variants will be found when the samples are

thoroughly investigated.

Samples: own finds if not indicated

otherwise.

Figs. 2-8:

Döhlen

basin, Freital

Fig.1: Pd/2.1, Perdasdefogu, Sardinia, 2009,

Fig.2: Bu4/31.1, found in 1996 on

the property of Lippert,

Burgk,

Bernhardts Weg 25.

Fig.3-6: Bu10/7, provided by H.

Nitzsche, Burgk,

Kohlenstr. 24, in

1998.

Fig.7: Bu8/18,

found in 1997 at Burgk,

Am Seilerschuppen,

and kept by U.

Wagner.

Fig.8: Bu2/5.1, found

in 1995 as one of the

first own finds on the "maggot stone" site,

on the property of W. Netzschwitz Kleinnaundorf,

Kohlenstr. 23, and

kept there.

* Uncommonly big and well-preserved specimens

of Psaronius,

the stem of several "maggot fern" species, are on display

at the Naturkunde Museum Chemnitz.

H.-J.

Weiss 2011, amended 2012

[1] M. Barthel,

W. Reichel, H.-J. Weiss: "Madensteine" in Sachsen.

Abhandl. Staatl. Mus. Mineral. Geol. Dresden 41(1995),

117-135.

[2] R.

Rößler : Der versteinerte Wald von Chemnitz, 2001.

[3] M. Barthel:

The maggot

stones from Windberg ridge, Germany.

in:

U. Dernbach, W.D.

Tidwell: Secrets

of Petrified Plants. D'ORO Publ. 2002. p65-77.

[4] E.

Zenker:

Scolecopteris elegans,

ein neues fossiles Farrngewächs mit

Fructification. Linnaea 11(1837), 509-12.

[5] H.-J. Weiss:

Beobachtungen zur Variabilität der Synangien des Madenfarns. Veröff.

Museum f. Naturkunde Chemnitz 25(2002), 57-62.

[6] M.A.

Millay, J. Galtier: Studies

of paleozoic marattialean ferns: Scolecopteris globiforma from the

Stephanian of France.

Rev. Palaeobot. Palyn. 63(1990), 163-171.

[7] M.A. Millay:

Study of paleozoic marattialeans. A monograph of the American species

of Scolecopteris.

Palaeontographica B169(1979),

1-69.

|

|

5 5 |

5

5

Figs.5,6: Chert face with

conspicuous array of Scolecopteris

synangia cross-sections on pinnules hardly visible

owing to decay [5]. Only the well seen cross-sections in Fig.5 have

been included into the drawing. Width of the picture 9mm. Photograph:

W. Schwarz.

Figs.5,6: Chert face with

conspicuous array of Scolecopteris

synangia cross-sections on pinnules hardly visible

owing to decay [5]. Only the well seen cross-sections in Fig.5 have

been included into the drawing. Width of the picture 9mm. Photograph:

W. Schwarz.

5

5